Ocho Kandelikas: A Song with a Story

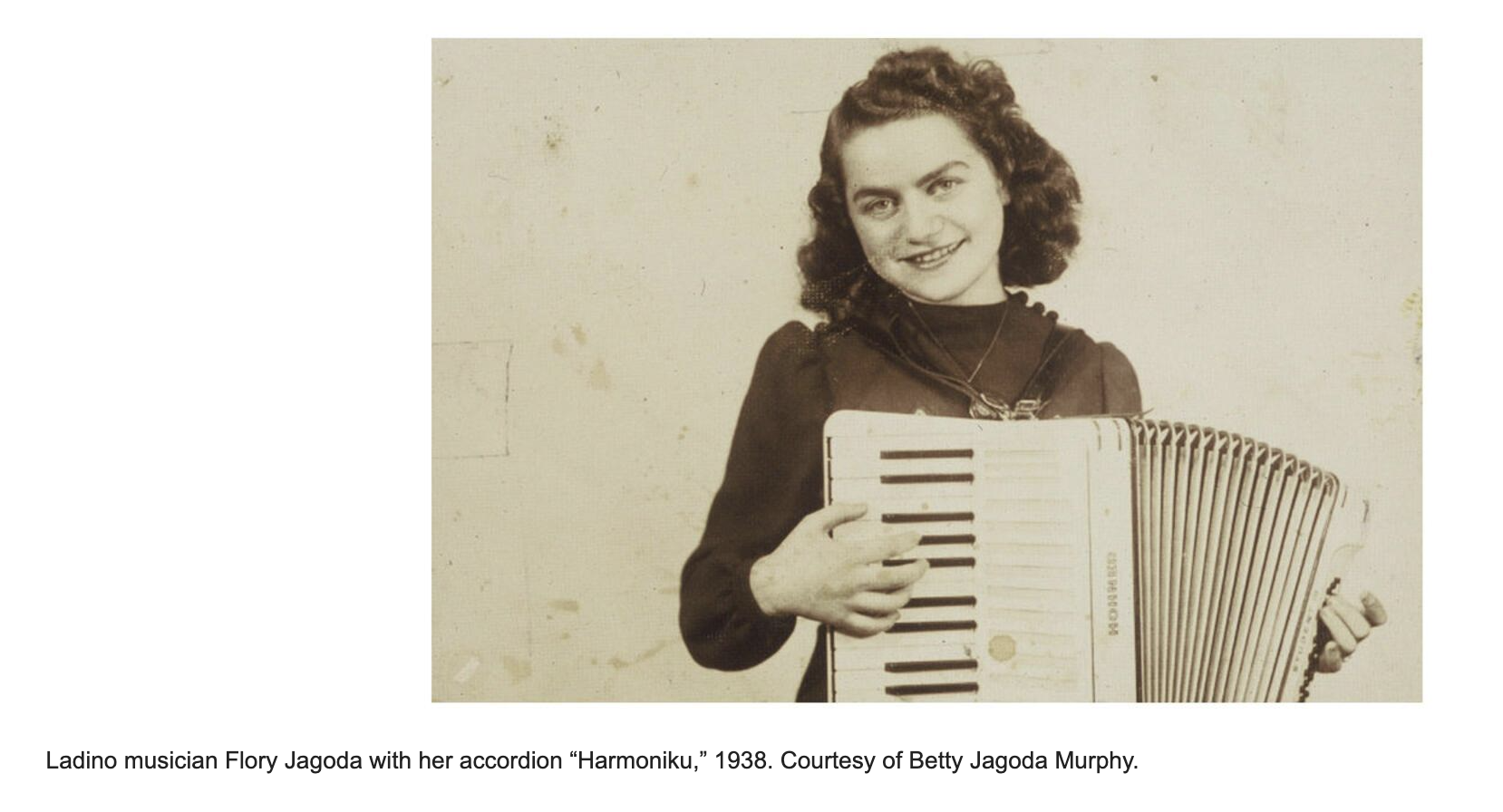

A sepia toned pictures from 1938 of young Flory Jagoda. She has brown-toned chin-length hair. It's curly and thick. Her round and angular face has dark eyebrows and she has dark eyes and a wide smiling mouth. She's wearing a dark top and she's holding an accordion. The caption reads, "Ladino musician Flory Jagoda with her accordion "Harmoniku" 1938. Courtesy of Betty Jagoda Murphy.

Ocho Kandelikas. If we celebrate Chanukah, there is a good chance we have heard - and maybe even sung - Ocho Kandelikas. (PSA "Ch" like Bach. It's a clear-your-throat hard 'h' sound.)

Well . . . this song has a STORY. And yes, it *is* a story of light that lasts, but it's not THAT story.

And . . . maybe you don't celebrate Chanukah. This story?

If you are here, I think it's a story you are going to want to know, too.

For one thing, it's about a woman who got married in a dress made from a silk parachute so obviously it has romance.

For another, it's a story full of horror, resilience, escape, and survival.

It goes like this . . .

Once upon a time, on December 21, 1923, a Sephardic Jewish baby was born in Sarajevo. Her mother, Rosa, named her Flora Papo and sang to her in Ladino - the language of the Sephardim. Ladino is similar to Spanish from the late 15th century. Rosa sang the songs of her own mother, a Sephardic folksinger.

Rosa Altarac, proudly traced their family history and their family's love of music from Spain.

As a child, Flory learned about the 1492 Edict of Expulsion issued by Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, about the Spanish Inquisition, and that the Sephardim were forced to convert to Christianity or flee the Spain they had loved for 700 years. Flory's ancestors journeyed from Cordoba to the then-welcoming Ottoman Empire and by 1565, a merchant trader named Avram Altarac lived in Sarajevo (Altaras in Spanish became Altarac in Bosnian). Time passed . . . and sometime before the 1800s, the Altarac family had relocated from Sarajevo to Vlasenica. We know because by 1884 they had established a successful store and vibrant trading business there. In the early twentieth century, Flory’s Nonu, Sambul Altarac, and his two brothers sat on the Vlasenica town council with the town’s Muslims and Greek Orthodox elders. The harmony between Muslims, Catholics, Greek Orthodox, and Jews throughout Bosnia lasted until it didn't . . . with World War II.

So, Flory was born in Sarajevo, but when her mother Rosa left her first husband they returned to the town of Vlasenica. There Rosa met and married Michael Kabilio, and they settled in Zagreb, Croatia, where Michael owned a tie-making business.

When the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941, Michael, with the assistance of a non-Jewish neighbor (who put her own life and her family's at risk by doing so), put 16-year-old Flory on a train to Split using false identity papers and removing the Jewish star from her coat. On the train she played her accordion all the way to Split. As the story goes, the other passengers and even the conductor sang along. Maybe that is why she was never asked for her ticket. Her parents joined her - and the other Sephardic Jews who had escaped the Nazis - in Split several days later. The Jewish refugees were taken to various islands off the Croatian coast. Flory's family was moved to the island of Korčula and they lived there until the fall 1943. After Italy capitulated, Jews on Korčula left by fishing boats for Bari, Italy, which had recently been liberated by the British army.

In Italy, working as a translator for the American Army, Flory met and fell in love with Jewish American soldier Sergeant Harry Jagoda. From what I've read, he fell in love right back and before long they talked with her parents about getting married. Harry, who was in charge of salvage, secured half a silk parachute and that material became Flory’s wedding dress and trousseau! On June 24, 1945, the American army hosted their wedding. Harry’s entire 225th Quartermaster Company and most of the Jewish refugees in Bari were in attendance. They had a homemade chuppah (wedding canopy), a Rabbi flown in from Naples, and an Army band.

Flory arrived in the United States as a war bride in 1946, going first to Harry's hometown of Youngstown, Ohio to meet his family, and later moving to Northern Virginia. Flory and Harry Jagoda, had four children: Betty Jagoda Murphy, Lori Jagoda Lowell, Andy Jagoda, and Elliot Jagoda (z"l). (z"l stands for zichrono livracha - may his memory be for a blessing. When it comes after a name, it means the person is no longer alive.)

Forty years later, on a trip to Vlasenica with Harry to visit Uncle Lezo’s daughter Berta (named for her Nona), Flory learned that Vlasenica’s 60 Jews, including 42 members of her Altarac family, had been rounded up by the Ustasha (Croatian fascist terrorist organization aligned with the Nazis), tortured, murdered in a ravine outside their village on May 6, 1942, and buried in a mass grave.

The Sephardic community of Sarajevo and its surrounding communities were nearly obliterated during World War II. Out of Flory's entire family in Vlasenica, only Rosa, Flory, Lezo, and a cousin had survived the war.

The title song in Flory's CD Arvoliko (The Little Tree) is about the tree that was the only marker of the mass grave until a memorial stone was placed in 2011.

Flory Jagoda's recording Kantikas Di Mi Nona (Songs of My Grandmother) are of her singing her grandmother's songs. After the release of her second recording, Memories of Sarajevo, she also recorded La Nona Kanta (The Grandmother Sings) - songs she wrote for her grandchildren. Ladino, or Judeo-Espanyol, the language of the Sephardim, is in danger of extinction, but it is experiencing a minor revival among Sephardic communities, especially in music. Flory was a leader in this revival.

And what of our Chanukah song - Ocho Kandelikas?

It means Eight Little Candles. The lyrics of the song describe a child's joy of lighting the candles on the Chanukiah - the Chanukah menorah.

She wrote it in 1983.

Ocho Candelikas is often performed in an Argentine tango-rhythm with accompanying accordion and violins.

Yeah, an accompanying accordion.

The same instrument she played all the way to Split.

In later life, Flory developed dementia and was unable to sing. She died at 97 on January 29, 2021.

We can read more of her story in the Jewish Women's Archive, and there are two documentaries about her - Key from Spain and Flory's Flame.

I told you this is a story of a light that lasts.

It is.

It's also a story of the commitment and dedication it takes to keep lighting and lighting and lighting that light.

This year Chanukah begins the evening of Sunday December 14th. Flory's story is one of our Chanukah stories. Let's tell it.