When Elmer Died

The first thing you need to know is this: I do not know when Elmer died.

Well, that’s not entirely true.

I know he died in October.

Seven months ago.

And also before you know that you also need to know that this is a draft.

A first draft.

I am writing without a plan and anything could happen.

The second thing you need to know is that I found out that Elmer died on Wednesday.

Not “a” Wednesday.

Wednesday.

Two days ago.

I found out when a neighbor posted in our Buy Nothing Group asking neighbors to please come take the things in the yard of 1370 James because a neighbor had died some time ago and otherwise all of his things would end up in a dumpster.

I was putting on my shoes when my neighbor made that post.

I checked my phone one more time for the addresses of the pick-ups I was about to make. See, I have a student who is currently getting ready to celebrate becoming bar mitzvah and his Gemilut Chasidim project (formerly known as mitzvah project) has been about inclusion and he’s been volunteering with Project Power and doing art projects and cooking with adults with disabilities. For the centerpieces on his day, I’m helping his mom put together boxes filled with art supplies that he’ll donate to Project Power afterward. Me being me, I started by asking for new and like new art supplies in my Buy Nothing Group. THAT is why I saw the neighbor’s post about the things at 1370 James and the dumpster.

I had five stops to make. It wasn’t hard to decide to stop at 1370 first.

Because that’s the thing, right?

I was about to invest some time helping some folks, easy enough to add a little more time helping someone else. I didn’t know the story of 1370 James, but a neighbor asked me - generally speaking - to come help. So I did.

When I arrived, a group of middle aged and white haired white women were sitting and standing among piles of books, furniture, cookie jars, kitchen items, lamps, a lemonader, an ice cream maker, clothes, fur coats, CDs, speakers . . . the stuff that fills up so much of our lives. And these things had stories to tell. For one thing, those cookie jars? A Black gospel singer. A Black mother reading her child to sleep. A Black chef holding a lobster on a platter. A Black woman in fancy clothes and a fabulous hat. And the books? True crime and mysteries, for sure, and then probably fifty African American history books, novels by Black authors, memoirs by Black authors. I looked around at all of us, at all of the white women standing among this Black elder’s things.

“It’s just so sad.”

“I can’t imagine what we could do with all of this.”

“How will we keep it from the dumpster?”

I introduced myself.

“Hi, I’m Amy. Are you neighbors? Did you see the post on Buy Nothing?

Turns out, all of us had seen the post, and we’d all responded in roughly the same way. We had shown up.

“What if,” I started, “what if we each put some of these things in our cars and bring them to our own houses, take pictures and post them in the Buy Nothing group and give them time for people to see the posts and come get the things? And what if we give priority to folks who are African American or who identify in some way as being part of the Black community?”

“I could do that,” said a woman with short brown hair and a minivan. “I could take some of the furniture.”

“I can get the chairs in my car,” I nodded. “And the cookie jars.”

“I could bring home some of this art.”

“I can get the kitchen things.”

So that’s what we did.

We filled our cars and took our pictures and made our posts and before long, another neighbor commented on them. She’d known the man who lived at 1370 James.

In the two days since, I've been going back and forth from his house to mine, posting in the Facebook group, talking with more neighbors than I have ever (Not just during the pandemic. Ever.), and meeting Black women in my neighborhood who are lovingly inheriting some of the pieces of this man’s life. This woman is looking forward to baking cookies and as she does so to send some blessings up to him. Another woman’s mom says whenever she makes lemonade she’ll say a prayer for him when she squeezes the first lemon and toast him with the first glass. A refugee family from Congo will feel more at home with some of his African art in their home.

No surprise, my favorite was the woman reading to a child.

I’ve also been learning something of his story.

And his name: Elmer.

Elmer has been living in our neighborhood longer than anyone I’ve met who knew him, and that goes back to the early-1990s. He was a social worker. He had mugs from an organization dedicated to the adoption of African American children. He would sit in his garage with the garage door open and read, and he would read anything. He was curious about law and politics, about people, and about the past. He’d been married. He’d been divorced. His partner of many years died eleven years ago and he had a stepson, but his stepson had no legal standing and anyway no one seems certain about their relationship. Someone said he had a daughter from that first marriage, but they weren’t close. Maybe estranged. Still, among his things was a kid-made painting.

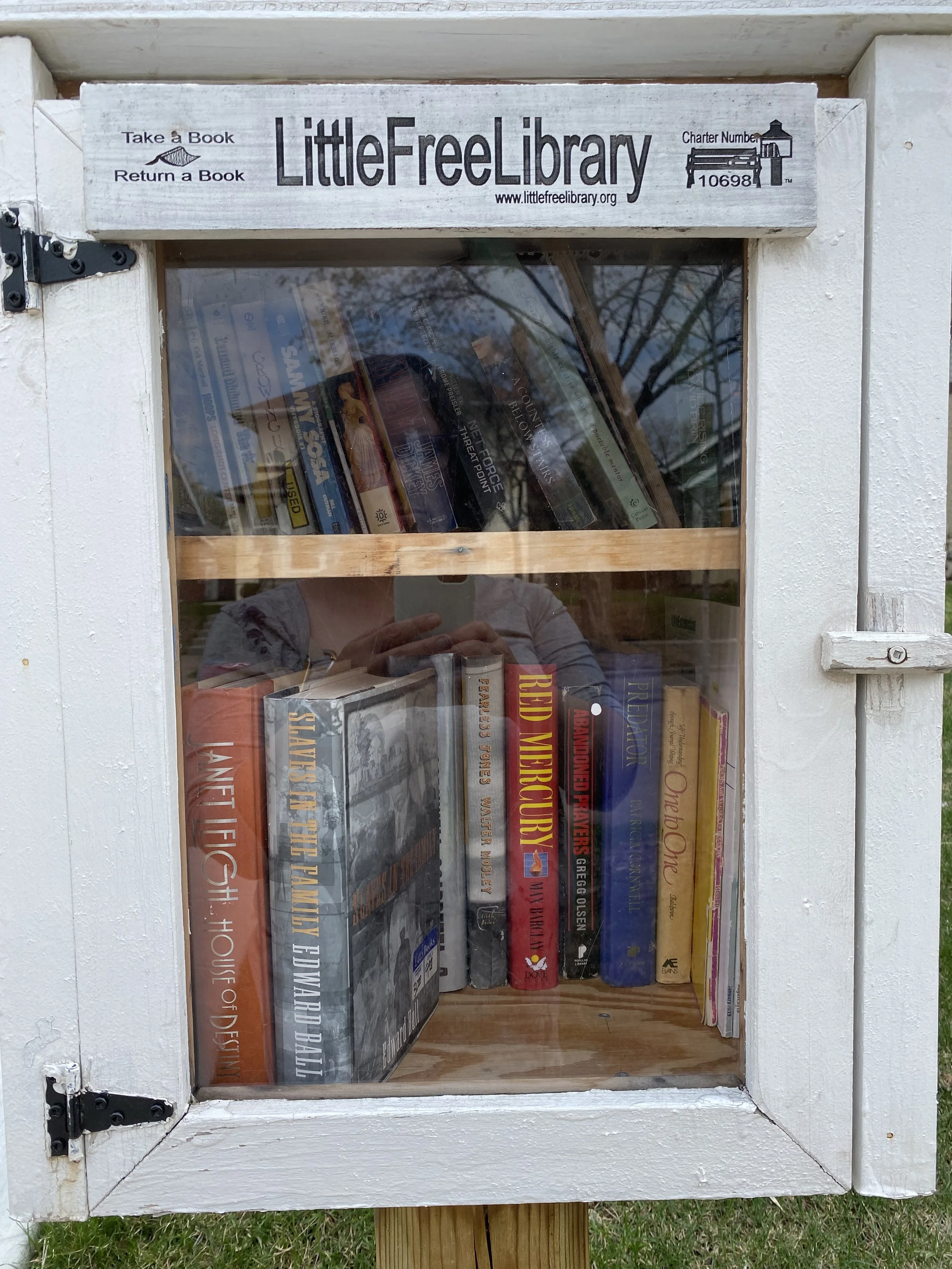

I took some of his books, the ones in the best shape, and wrote on the inside of the front cover. I drew a heart and wrote his name and then put them into little libraries on my street.

Elmer wasn’t done with me yet. I felt compelled to go back yesterday after morning minyan when, by the way, I said kaddish for Elmer even though it wasn’t his yahrzeit - the anniversary of his death. I just needed to. For me. I needed to say his name in a community. So I did. And then? I filled my car again. I posted more pictures.

I took responsibility for a probably fox-fur wrap. It might be from the 60s. I’m no expert, but from looking online that seems about right. I posted pictures and a young, queer, Black actor who is friends with a former student of mine wanted it. Really wanted it. I told him when he picked it up I’d mask up and come out to meet him, and if he’d also mask we could talk for a few minutes. He arrived in a mask. Chesed everywhere.

Friday morning, this morning, when I went over to the house there were just a few big things left. A dresser. A shelving unit. An old bike. A printer no one will likely ever use again. A few big things. And more boxes of books. So many books. They were picked over and had been lightly rained on, and many really needed to be put out of their misery at this point . . . but it seemed like many of them were still reasonably readable. I took pictures of the big things and gave them each their own post on our site and got to work on the books, putting the good ones in bags in my car and the rest, wet and dirty, I held with care and then helped find their way to the dumpster. Neighbors came out of their houses to thank me. People driving by slowed down and asked if I was “Amy from Buy Nothing.” Yes, that’s me, I said. Someone stopped by and asked if I’d known Elmer. No, I said. We only just met on Wednesday. She looked at me like I was peculiar and continued on her walk. Fair.

Then an older white haired white woman, maybe late 80s, with a walker, came out and walked over to me. I was wearing my mask, of course, and had tears in my eyes that kept slipping out and down my face.

“Who are you?”

“Amy. A neighbor.”

“Oh, you live on our street?”

“No. I live about a mile north. Up that way.”

“You family?”

God bless her.

“No.”

“I’ve seen you out here every day. Why are you doing this?”

I felt tender. A bit raw.

“Do you want the real reason or the Minnesota reason?” I asked.

“What do you mean?”

“Oh,” I shrugged a tear with my shoulder, “Do you want my story, or do you want something else that’s also true? I’m a neighbor. I’m just trying to be a good neighbor to a man whose things aren’t trash.”

“I think . . .” she paused, “I think I want your story.”

“Okay. Well, here it is. Almost 12 years ago, on May 12, 2011 I had a bone marrow transplant after being treated for leukemia. I was really sick. I could have died. Death was far more likely than life, actually. And I had an apartment and a life full of things. Brimming with things. I had a bed I loved, and a dresser. I had an electric teapot someone I really love had given me, it had been hers. I had . . . you know . . . I had things. And I didn’t die, but I was really sick, and I needed to move out of my apartment and I didn’t have anywhere for many of my things to go. Some, but not many. And friends and people who knew me and strangers helped out and found my things new homes. And I was alive and in a bed, but I didn’t really have a lot of say and I had no control. I know many people really honored my things, but unfortunately I also know not everyone did. One of my students helped with my books and gave them a lot of love. On Wednesday, when I showed up and I met the other women who also showed up, and the men whose job it was to clean out everything from Elmer’s house, and I saw the dumpster, I just knew that the things of a person’s life are not trash. I didn’t know who he was, I didn’t know anything about him. I just . . .”

“Yeah,” she said.

I just had to, I thought.

“Yeah,” I said. “The anniversary of my bone marrow transplant is next week. How could I not do this?”

“Well,” she said. “He wasn’t always the nicest person on the block. Not that he was mean. You know, he kept to himself. He’d wave, maybe, but he didn’t ever really want to talk to me. He was kind of cantankerous sometimes. Near the end I’d hear him yell at workers who had just come to help, but that’s how we get sometimes. And then, he was also such a good man. Back when he could, he would always help when someone needed help. You could just tell he didn’t care if he liked you, he’d help you if he could. I don’t mean that critically, I mean him liking you just wasn’t why he was helping or not helping.”

I smiled. Just yesterday I was telling someone that I’ll take good people who do the right thing and help other people over “nice” people any day. We chatted a few minutes more and she made her way back to her house.

Okay, Elmer, I thought. Maybe you are actually pissed as hell that I’m touching all of your stuff. That’s okay. Be mad if you need to be. I’m going to keep going anyway, and who knows, maybe you aren’t.

I finished getting the 200 or so still readable books in my car and tidied up what was left in the yard, drove around the neighborhood little library to little library and filled them all. It took another 90 minutes, and now I’m sitting at my desk and it’s pouring outside.

Not just raining.

Pouring.

At least, that’s how I feel about the water falling from the sky.

I also feel pleased about my time with Elmer’s books and how they are safe and sound and tucked in and waiting for whoever will read them next.

As we count the omer and make our way from Passover to Shavuot, today is day 29 and we are in the week of hod (humility) and the day of chesed (loving-kindness). That feels about right. Humility, of course, is about taking up the right amount of space - the space that is ours to take up. It’s not about being small, or about not being big, but about being exactly “us” sized in the moment and in the place. Chesed, well, that’s the kind of love that’s kind and kindness that’s loving that isn’t necessarily about being nice but is absolutely about doing good. Thinking about my day it tracks in every direction.

Then it occurred to me, rather late in this process to be honest, to pause in my writing and reflecting and wonder what Emor, this week’s parsha, might have to say about this particular part of my week. I read it on Tuesday and thinking about it just now nothing sprang to mind, but then I read it again and laughed out loud. Actually. It begins like this:

“Adonai said to Moses: Speak to the kohanim, the sons of Aaron, and say to them: None shall (come into contact with and become ritually impure because of) any dead person among his kin, except for the relatives that are closest to him: his mother, his father, his son, his daughter, and his brother, and also an unmarried sister.” Leviticus 21:1-2

These Temple priests have a job to do and they need to be ritually pure to do it. Contact with death (among other things) can render people and things ritually impure and then a kohain wouldn’t be able to do his job. The Torah portion goes on to include instructions about not profaning sacred places and sacred donations and sacred times. Basically, do right by the places, the donations, and the season . . . or the day. All of this underscores the other rules that we know, rules about doing right by the person who has died. I was taught that the last mitzvah we can do for someone is bury them with dignity. We honor their body, the vessel that allowed their soul to be animate in the world. We guard their body from death until burial. And after they are set into the ground, we shovel earth into their grave with an upside down shovel because it is a task we would never rush.

I won’t make light of Emor, there are many challenging - even shocking - verses.

But seriously.

The third thing you need to know is who Tevye is and that I am not a kohain, which means if you, like way too many of my students, have never seen Fiddler on the Roof, you really need to get on it. Inside my brain right now is my own version of a Tevye and God convo. As for not being a kohain - a priest, I don’t have that communal role, not least of which because we no longer have a Temple, but also because I’m not descended from the kohanim. I could be, and if my last name were Cohen or Cobin or something I’d look into it, but I’m all Elperins and Friedlanders and Bernsteins and Stotskys on the Jewish side of my family. Ariel is my Hebrew name and I chose it as a last name for myself. My mom created her last name out of my great grandmother’s first name - Rose - and became a Rosen. The priests are my ancestors in the “ancestors of my People” sense, but not in a personal sense. And Elmer? Also not a kohain. Again, could have been, but I know his last name now, I saw it on a medical document folded and stuck in a book like a bookmark, and anyway among his things the man had Christian music and books and those laminated prayer cards and while not entirely dispositive I feel pretty confident that among the things Elmer may have been, Jewish isn’t one of them. So not personal for him, either.

Okay, I think to God. Okay. So I’m not a kohain and the rules don’t apply, right? And anyway, it’s not like you sent me over to be near his corpse. And You’re right, I am getting attached even though I’m not remotely related. At all. In any way. Even if a neighbor who knew Elmer thought it might be possible. That’s not a problem for you, is it? That I get attached? I think You are the reason I ended up at Elmer’s house in the first place. I also suspect you have something to do with my feeling attached to him. These degrees of relationship the Torah sets up? Absurd. Way too heteronormative. That’s not the way life is actually lived. You know that, right? It’s people who get it wrong? I hope so. Because Devlin . . .and my thoughts trail off as I remember my godson of blessed memory. Yeah. Because Devlin.

So what? Your point is that related or not Elmer and I are kin?

You think I don’t already know that?

You have another point?

And, Elmer? Are you finished with me yet?

Not hardly. I kept one thing of Elmer’s.

It’s an angel statue and now it lives in our garden.

And okay, I might also keep a lamp.

I think Elmer is here to stay.

Rabbi Morris Allen teaches that one of the ways we can find meaning in our lives is by looking at the Torah portion for the week of whatever thing has happened for which we are looking for meaning. Before my bone marrow transplant, Rabbi Allen and I talked about how it matters that my birth parsha is mishpatim, after all there is an angel going ahead and making the way ready, and that it will matter what my death parsha is, too.

I tried to find an obituary for Elmer, tried to find out when he actually died.

I wasn’t able to.

Maybe I’ll keep saying kaddish for him on the 13th of Iyar.

Maybe his death parsha is Emor.

There is a fourth thing you need to know, and like the rest of what I’ve written it’s not really about Elmer, because I didn’t actually know Elmer. I only have ideas of Elmer, illusions of Elmer.

It’s about me.

During my treatment 12 years ago I more than once felt like I was losing my muchness. Muchness is an Alice in Wonderland thing. Muchness is that fire of being exactly who we are. Fighting for my muchness was harder than fighting for my life. It still is. Insisting that my providers see me as me and not just as their patient, insisting that people who care about me see me as me and not just some illusion of me. Back then I think the illusion was that I was this brave person facing her own mortality and being inspiring and writing about it on Caring Bridge and now . . . well, I don’t even know what the illusions are, but sometimes I can kind of smell them. Not that I wasn’t brave. I was all kinds of brave, not least of which because I was also really scared. And not that I’m not brave now. Or scared now. I absolutely am. Muchness isn’t bravery, but it takes bravery. Muchness, I think, is hod, it’s humility, it’s taking up exactly our space in whatever space we find ourselves in a particular moment.

And it’s almost Shabbat, and this has all been a first draft, as rough as it gets, and I didn’t set out knowing what I wanted to say exactly and I still don’t, but I do know that I need to say it now. And I know it’s about me. And maybe it is also about Elmer. And it’s about death. And it’s about books. And it’s about cookie jars. And old fur wraps. And neighbors. And community.

It’s about how on May 12th I get to celebrate Valinor’s cells finding their way to me from Germany and flowing through my body and finding my bones and setting up shop and making the marrow that is making my blood and reminding me that I am a walking, talking, sometimes dancing in the kitchen miracle. Because I am alive. Not only because I’m alive, though.

Can I tell you that more than sometimes, especially here in Minnesota, I feel like I am way too much? Not just a little too much. Way. A lot too much.

I have a good friend who says she knows extra when she sees it because she’s also extra. She says I’m extra. She says it as a compliment. I take it as a compliment. I don’t feel too much when I’m with her.

The past three days have been me being my very particular flavor of extra.

I have felt the most myself that I have felt in a long time. Even like I found some piece of me that I’d forgotten about, and not only because Elmer’s been with me everywhere I go and I like the company. I’ve cried in public. I’ve shared a piece of my actual story with strangers. I’ve planned and organized centerpieces for the bar mitzvah of someone else’s kid and she and he are both glad I’m doing it. I’ve led minyan and talked about and taught about exactly what I have to share with the world - the best that I have to share with the world. I made time to hang out online with an immunocompromised woman in Chicago who has life threatening reactions to vaccines and who has been made to feel that the problem is her, that her existence is a burden, and that she has to compromise her safety - emotionally and physically - for other people’s convenience and comfort. She. Does. Not. Are there consequences to refusing to live by those social rules? Absolutely. Are there even bigger consequences to complying with them? Of course there are. I made space for her to cry, and I just made space. For her. All of her. I Don’t know her, either. She’s someone who knows a friend of mine and who needed to talk with someone who would get it. I’m someone who gets it.

Like I get that Elmer and I are kin.

Like I get that the kindnesses we can do for one another are expansive and never ending.

Like I get that being nice is not nearly as important or useful as doing good.

Like I get that somehow all of this and all of us are connected.

Like I get that it’s hubris to think that Elmer got all of that, too, and still I’m sure of it.

As sure as I’ve ever been of anything.

Because this man, who someone said never wanted anything more than to bring people together and to help people, brought together a whole neighborhood seven months after he died.

Shabbat Shalom.

*This really is a rough draft. Please forgive typos and formatting issues.